Benin is a West African country that is home to nearly 14 million people, about one million more than the population of Pennsylvania. For nearly two centuries, it was at the heart of what was known as the ‘Slave Coast’ due to the number of people who were purchased and trafficked from the region. In 1894, due to France’s takeover, Benin became part of French West Africa and didn’t gain its independence until 1960.

Under colonial rule, French became the official language of Benin despite the existence of several native languages. For those who could afford formal education, reading and writing were taught exclusively in French which left literacy rates low to non-existent among native language speakers. Since gaining its independence, Benin has steadily expanded access to public education and as of 2013, UNESCO estimated that 54% of Beninese children were enrolled in secondary education.

Despite these developments, some languages native to Benin that predate French colonial rule are in danger of going extinct. Anii, for example, is spoken in a number of villages in Benin as well as in neighboring countries Togo and Ghana by roughly 50,000 to 65,000 people according to recent estimates. Because of the relatively low number of speakers, and Anii’s classification as a language island – meaning it is surrounded by seemingly unrelated languages – the Endangered Languages Project has classified it as vulnerable.

There are efforts underway, though, to document and preserve the Anii language. Penn State and Schreyer Honors College are doing important work to make sure that is possible, and for one Schreyer Scholar, a summer in Benin proved to be an invaluable learning experience.

“Across the globe, languages die every year as a result of colonialism, imperialism, war and other tragedies. I believe that everybody should have a right to speak the words of their ancestors into the modern day, and I wanted to help the Anii speaking communities of Benin do so,” said fourth-year Scholar Greg Costanzo.

Costanzo was inspired to travel to Benin this summer to take part in Penn State linguistics professor Deborah Morton’s Anii language project. Morton has published research on Anii as far back as 2012, and this summer her work focused on the previously undocumented North-Central (NC) Anii dialect.

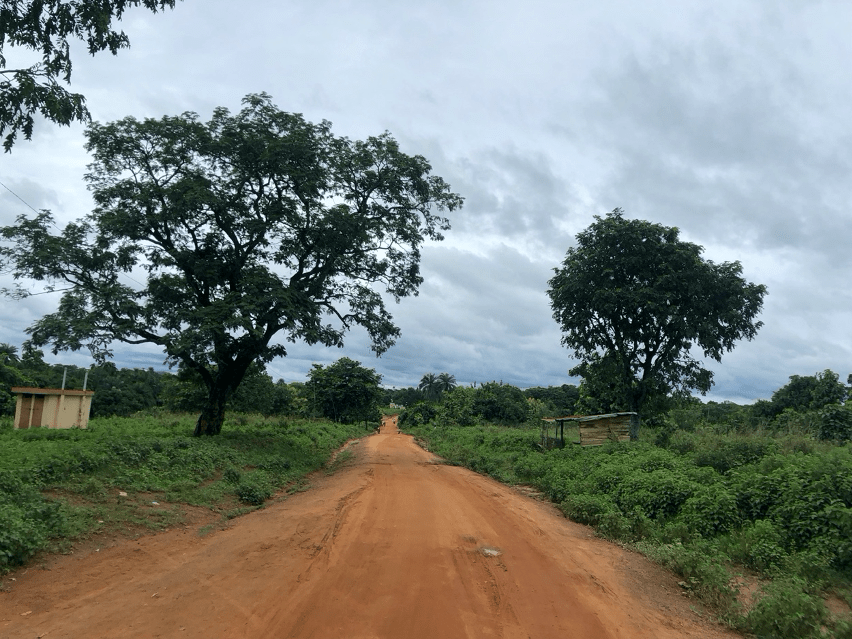

“The NC dialect is spoken in the Beninese villages of Penessoulou, Penelan and Nagayile, and has never been studied academically,” explained Costanzo. “This dialect is also at risk due to the movement of Anii standardization. Therefore, our study’s goal was not only to document the NC dialect but also to include it in the Anii language preservation efforts as a whole.”

He explained that his team’s first step in documenting this dialect was to build a corpus, which is a database of audio recordings and transcriptions of language data – essentially conversations between people. Thanks to his fluency in French, Costanzo could speak with Anii/French bilinguals and “gather a broad set of audio data as well as the specifics of verb tense and aspect.” With that data they were then able to start parsing the differences between NC and other Anii dialects, and the early results proved to be encouraging.

“It seems that while [NC’s] grammar is very similar, the vocabulary can be quite different, and many words are pronounced differently despite appearing to share a root,” Costanzo said.

He also took a particular interest in how, in the NC dialect, tones were used to alter the meaning of words and phrases.

“Learning how grammatical tones manifest themselves in Anii was fascinating,” he said. “In English, we put ‘will’ before an infinitive verb to make it future tense. In Anii, though, a high tone on a verb appears to make it future tense. Additionally, certain high tones on words can help distinguish between when a person is not sure something has taken place or if they do know that something has happened.”

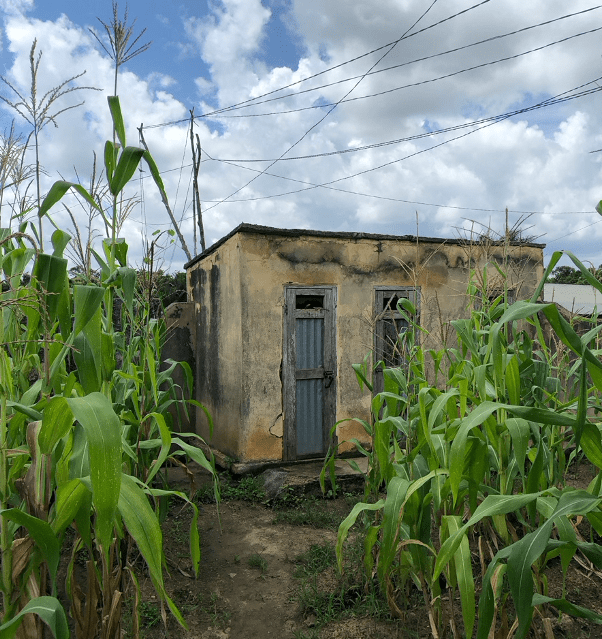

The team from Penn State collaborated with a Beninese non-governmental organization (NGO) called Lingo – Bénin that includes linguists, teachers, religious leaders and other community members who want to promote literacy in the area. Their work focuses on creating print and online resources to help people read in the Anii language.

Costanzo said that he worked closely with three residents of the village of Bassila during his time in Benin, and that they played integral roles in helping his research.

“Moumouni and Malokiya are farmers who have a great deal of experience working with linguists and have close ties to the villages whose dialects I studied,” he said. “Moumouni is also an artist and graphic designer while Malokiya is an Islamic cleric. They helped me coordinate meetings with elders and community leaders so that I could gather data by recording personal stories and local folklore.

“I also worked with Elysée, a musician and church leader, to help the NGO with its general operations,” he added. “Together, we translated Anii proverbs into English, French, and Italian for the online website, as well as translated sets of Anii vocabulary into English for the organization’s online dictionary.”

A triple major set to graduate in spring 2024 with bachelor degrees in linguistics, biology and psychology, Costanzo was able to take on global learning opportunities thanks to Schreyer resources that are made possible by philanthropy. His project in Benin was funded in part by Schreyer Global Ambassador Grants and an Erickson Discovery Grant from Penn State. A similar trip to study linguistics in Colombia was made possible by the Honors College’s travel fund. He encourages fellow Scholars to “take advantage of Schreyer’s generous funding” and grow by pushing past their comfort zone.

“I highly recommend traveling to where people will not speak English and where your ideas of norms and conditions will be challenged,” Costanzo said. “It will help you develop a high degree of tenacity and strength, as well as the perspective and wisdom to understand how humanity outside of our culture lives.”

As he navigates his final year as a Penn State student, Costanzo has taken time to reflect on his summer in Benin and how the trip continues to impact him now that he has returned home. He noted that it helped him better understand how governmental decisions and economic policies – both shaped by citizens’ votes – impact developing countries. Costanzo also said the experience left him feeling humbled and has led him to “meditate deeply” on his own privilege.

A son to Penn State faculty members, Constanzo started building his global perspective at a young age. He traveled with his parents when he could and also spent his final year of high school in Deyang, China – an industrial suburb of Chengdu – taking part in an exchange program. He still calls that trip the most influential of his life. Those experiences outside of the U.S. coupled with academic interests that cover STEM and the arts have given Costanzo a clear picture of what he wants to do post-graduation.

“I will likely be looking for work in the life sciences sector because it is broad and international and includes areas like pharmaceuticals, healthcare and biotechnology,” he said. “I would like to find myself in a position where I can act as an international coordinator for healthcare or pharmaceutical firms, or even eventually end up working with or at the World Health Organization. That way, I could work my way up to a position where I can promote better access to medical care and medicine in places like Benin while also using my language skills and tapping into my experiences from working abroad.”